Art for the Frozen Sea with Mary Hazboun (Special Issue)

"I want to highlight the psychological aspects of living as colonial subjects,"says the visual artist.

Mary Hazboun’s art series, The Art of Weeping, invokes visceral emotions. Drawn in black and white, her pieces typically feature feminine figures, devoid of facial features apart from a single piercing eye, their bodies contorted and cramped. Born in Bethlehem, Hazboun spent her first 21 years living under the Israeli occupation until she and her immediate family relocated to the United States in 2004. In 2015, Hazboun began her artistic journey while in graduate school for Women’s and Gender Studies.

“I started doodling in class to ease the traumatic flashbacks I was experiencing while reading materials that discussed military and gendered violence,” she explains. Hazboun lives with complex trauma, and her work grapples with its impact on her body. Research shows that trauma can trigger disruptions in the immune system, heart conditions, depression, etc. It forces a transformation within the body that causes an alienation of the self that Hazboun is familiar with. “I draw an emotional state,” she says, “I am working through what it means not to feel at home in your body.”

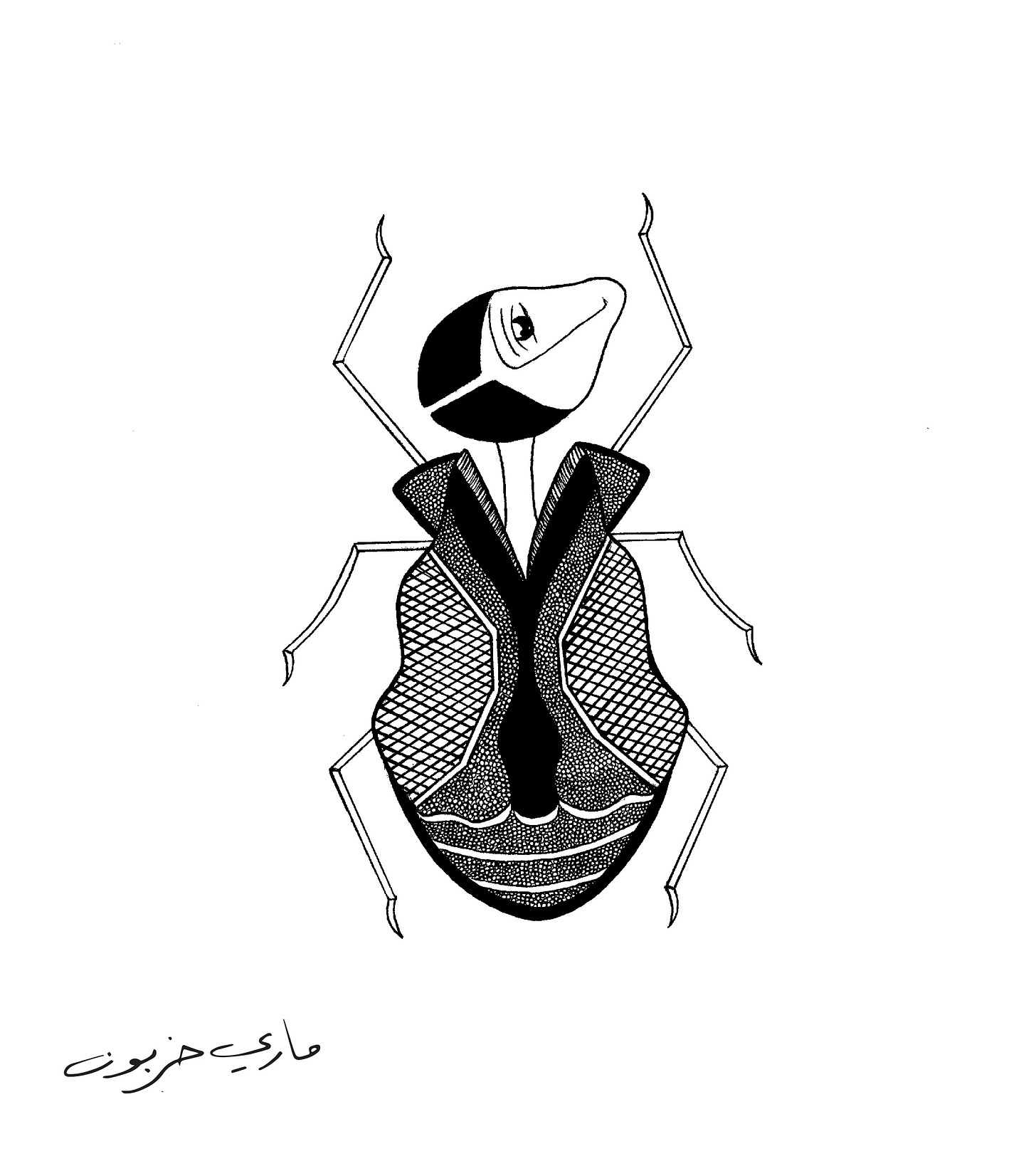

Her piece, Kafka, depicts this examination of the body and transformation, alluding to Frantz Kafka’s most famous book, The Metamorphosis, about the life of a traveling salesman, Gregor Samsa after he awakens to find he had transformed into an insect.

In his new body, Samsa is disconnected from his family and concealed from society. He struggles to reconcile his transformation with his environment - suddenly, he couldn’t move, eat, communicate, or do much of anything the way he used to. Hazboun resonates with how Kafka writes about strangeness and alienation and uses symbols to reflect these themes in his books. “I consider him (Kafka) my artistic soulmate. His work is dark, and so is mine, but it is necessary,” asserts Hazboun.

Apart from being an intrinsic part of her healing journey, Hazboun’s art reflects on the reality of living under military occupation. Since the occupation began during the first Nakba in 1948, Palestinians have been systematically displaced and ethnically cleansed, living under the constant threat of violence.

Hazboun herself experienced the Second Intifada, a period characterized by alarming violence that lasted from 2000 to around 2005. “The Israelis invaded the town, they forced a severe curfew, they were bombing buildings next to our home,” Hazboun recalls. As an effect of complex trauma, her memories of these scenes are fragmented, reflected in the minimalist style of her art.

“The emphasis in my work is on how the elements of the military occupation - the barbed wire, the separation wall - our bodies become an extension of them,” Hazboun expounds, “our access to roads, to healthcare, to our families are all dictated by the war machine.”

Today, due to the ongoing genocide, Palestinians both under Israeli occupation and abroad are experiencing a level of alienation that is devastating to contend with. “Even if I am not there, the occupation lives in my mind,” says Hazboun, “and I want to use my work to highlight the psychological aspects of living as colonial subjects.”

Making her art has helped her navigate the expanse of her grief, and she has built a community around The Art of Weeping, although it was complicated to deal with her work gaining recognition at first. “It took sweat, blood, and tears for the art to come to life,” reveals Hazboun, “and when people started recognizing my work, it was very raw, and I wasn’t ready.” However, seeing the responses from people connected with her art makes her feel grateful and less alone.

In fact, for the last three years, she has received requests from people who want to tattoo her art on themselves - people from different backgrounds who see themselves and their experiences with dealing with trauma reflected in her work.

“Till this day, I’m speechless that it resonates with people so much that they want to ink my work,” says Hazboun, “they could just do it, and I’d never know, but most people have been very intentional about it.” When people reach out to her, they often tell her personal stories and explain their desire to get her work tattooed. After the tattoo is complete, Hazboun shares them (with expressed consent) on her social media. It’s become a very heartwarming and affirming tradition for her.

“I was alone throughout my healing and recovery journey, and I understand how isolating trauma can be,” Hazboun remarks, “the more stories that people share with me, I realize this is my soul work.”