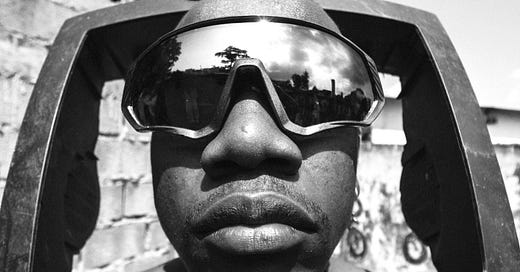

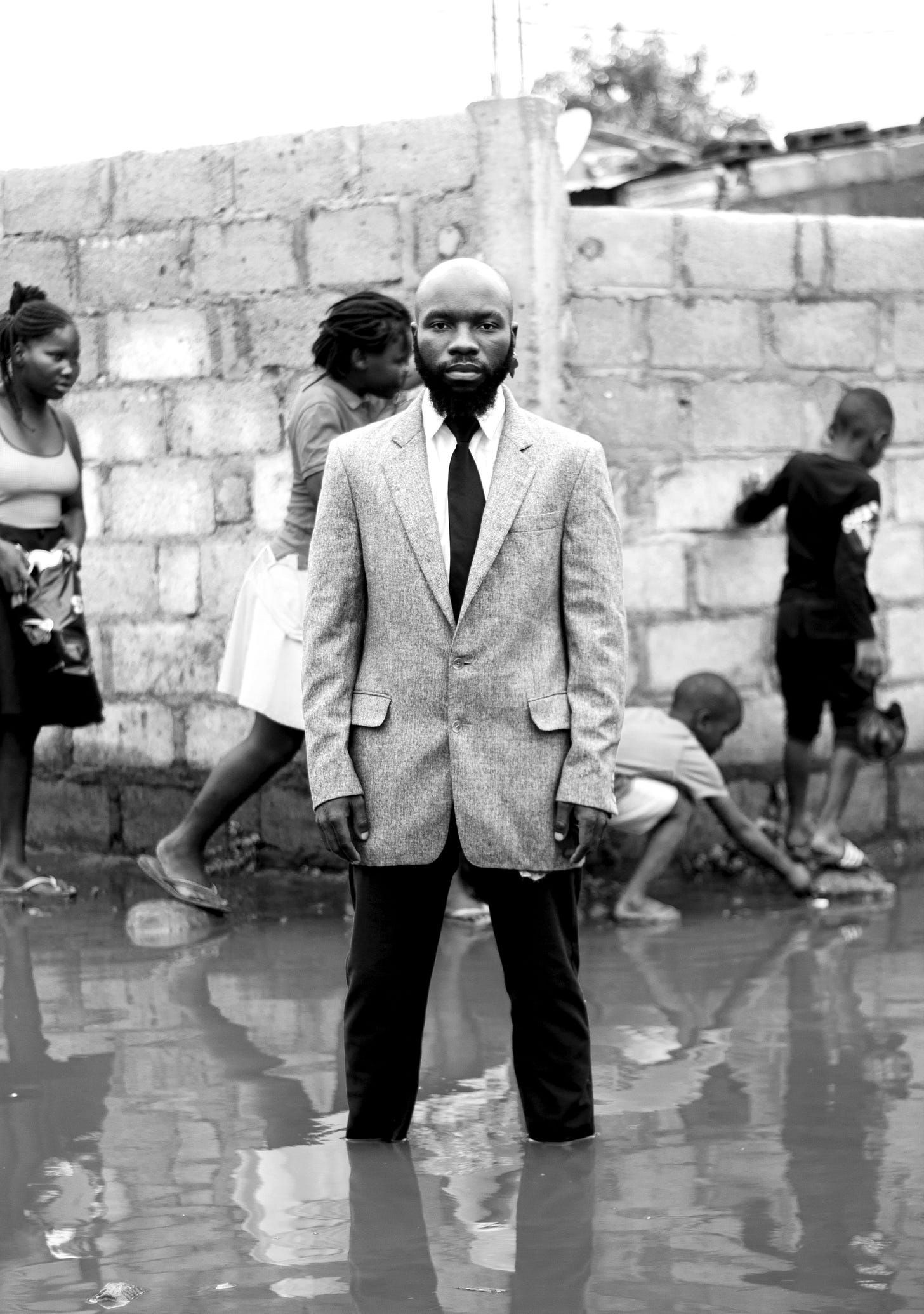

Contemporary African photographers are taking big swings, using their lenses to showcase African people and places in dynamic and often thought-provoking ways. “I often use actors in my portraits, I find that they immediately know to embody a character,” says Ildefonso Colaço, a 26-year-old photographer based in Maputo, Mozambique. The images – a well-suited man sitting in a trash dump, a woman striking a demi plie ornamented with colorful bifocals, two male figures coated in streaks of white flaying their limbs in a field – are definitively evocative. Subjects are caught in Lecoq-style movements: miming, elongating, contorting.

His portraits marry theatre and photography, while simultaneously throwing a monkey wrench at parameters of aesthetics. He toggles with notions of gender norms. He pokes and prods at the absurd. “I took that picture in the trash dump in my neighborhood. No one wants to take pictures there, but the dump is a place. Do these places also not have intrinsic worth?” Colaço questions. In his city, red-tinged dirt roads and corrugated iron houses are fixtures of the environment, and he amplifies these elements and incorporates them into his portraits in a way that inadvertently disrupts how people have been conditioned to see them by mainstream media.

Colaço’s style evolved from studying the work of post-colonial African artists across all mediums. “It wasn’t until that wave of independence movements started happening that Africans started to be empowered to tell stories about ourselves in the ways we want,” he explains.

During the colonial era, there were a few photo studios spread out across the continent spearheaded by Indigenous Africans/Afrodescedants. However, the more widely distributed photos from the region at the time were of the Tinne and Foà variety, and their photographs came with complicated subtexts. So, during the post-colonial era (the 1960s–1980s), Africans were tangling with the notions of ‘Africanity’, identity, and the transformation spurred by the changing times. Some of Colaço’s major influences like Malick Sidibe and Ricardo Rangel captured how people were contending with the changes in their own backyard. Colaço views himself as following in similar footsteps.

Alongside portraiture, Colaço also does street photography. While his portraits are theatrical – a mirror that inadvertently spurs questions about customs, norms, and aesthetics to the audience, his street photography does the same but through a pointedly more realistic perspective. “Photography is a form of expression, but it is also documentation. In Mozambique, we have some archives, but not a lot–especially until recently. It’s a big question at the center of my work.” he says.

He believes there’s room to capture more of life in the country on a Tuesday. In his photo walks, he’s been able to capture niche subcultures around the city that some would find surprising. Colaço describes one of his favorite things to do is photograph the skaters that gather at a skatepark in the heart of the city, “Since 2001, there’s been a skateboarding culture here, but people (outside of his area) don’t know that.”

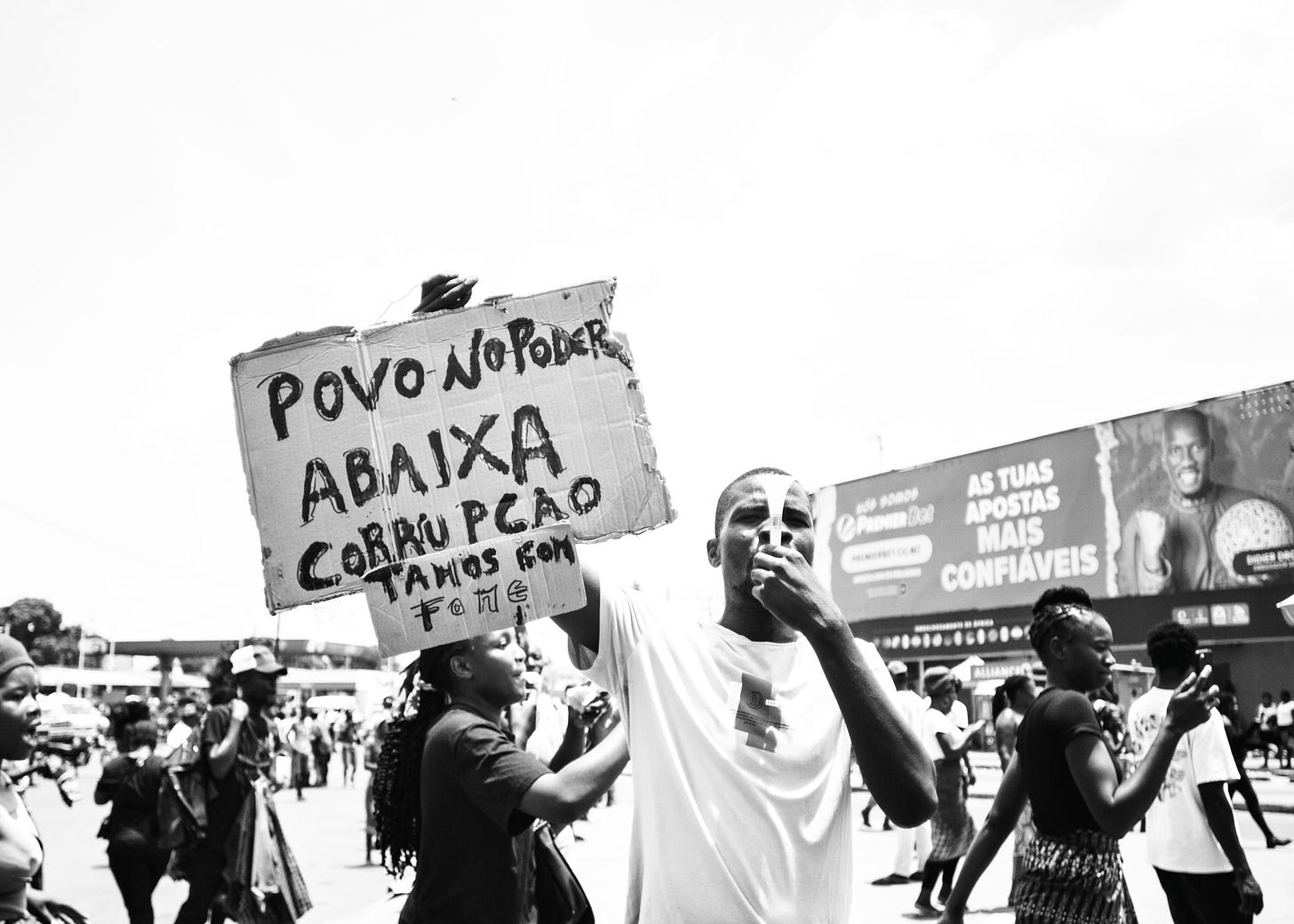

Sometimes, Tuesdays can be particularly feverous. In the last few months, some of Colaço’s recent pieces have been tied to the political demonstrations and protests happening in Maputo since the aftermath of the 2024 presidential elections in October. Since Daniel Chapo, of the ruling party Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), was declared the winner, there have been a string of protests calling for a recount.

Colaço has been in the middle of these demonstrations. In fact, he is adamant about being a participant as a point of principle, “I am participating with people, I don’t take pictures and leave because I’m not an outsider.” As the demonstrations unfolded, he noticed some discrepancies in how they were reported by the mainstream media. “I was at these protests. I saw what happened. Then, I saw their narrative (on the news), and that wasn’t what happened,” he asserts.

Censorship is an unfortunate feature of Mozambique’s political history. Colaço’s inspiration, Mozambican photojournalist Ricardo Rangel, was subject to censorship under the Portuguese government for his work in Tempo documenting the realities of urban life in Maputo. Although Colaço doesn’t consider himself a photojournalist, he believes this history of censorship and manipulation of the truth makes the role of photography even more imperative.

“It’s important to document the facts, I’m here recording this so you can’t manipulate it,” he expounds. The photographs act as a record of events; although there are no guarantees it changes anything about how people view the situation, the mere fact of its existence is already hopeful.

Colaço aims to make sure these images – portraits, pictures of daily life, pictures of protests, etc– exist and can exist tangentially. They are needed to show the full expanse of the human condition in his society. When asked about why he sometimes captures portraits that blend notions of gender – men in dresses or women in menswear – he asserts it’s not for an underlying message, “I’m not worried about addressing (commenting on) norms, the thing is that it exists, there are people who dress like that.”

And maybe people expect pictures of protests instead of high-drama portraiture from Mozambique. The colonial gaze has warped many people’s perception of what it should look like to live there. Yet, these images of expression and vivid reality, the woes, triumphs, the mundane, the beautiful, and the ugly, all say something about what it means to live in Colaço’s reality, and they all have their place in the record.