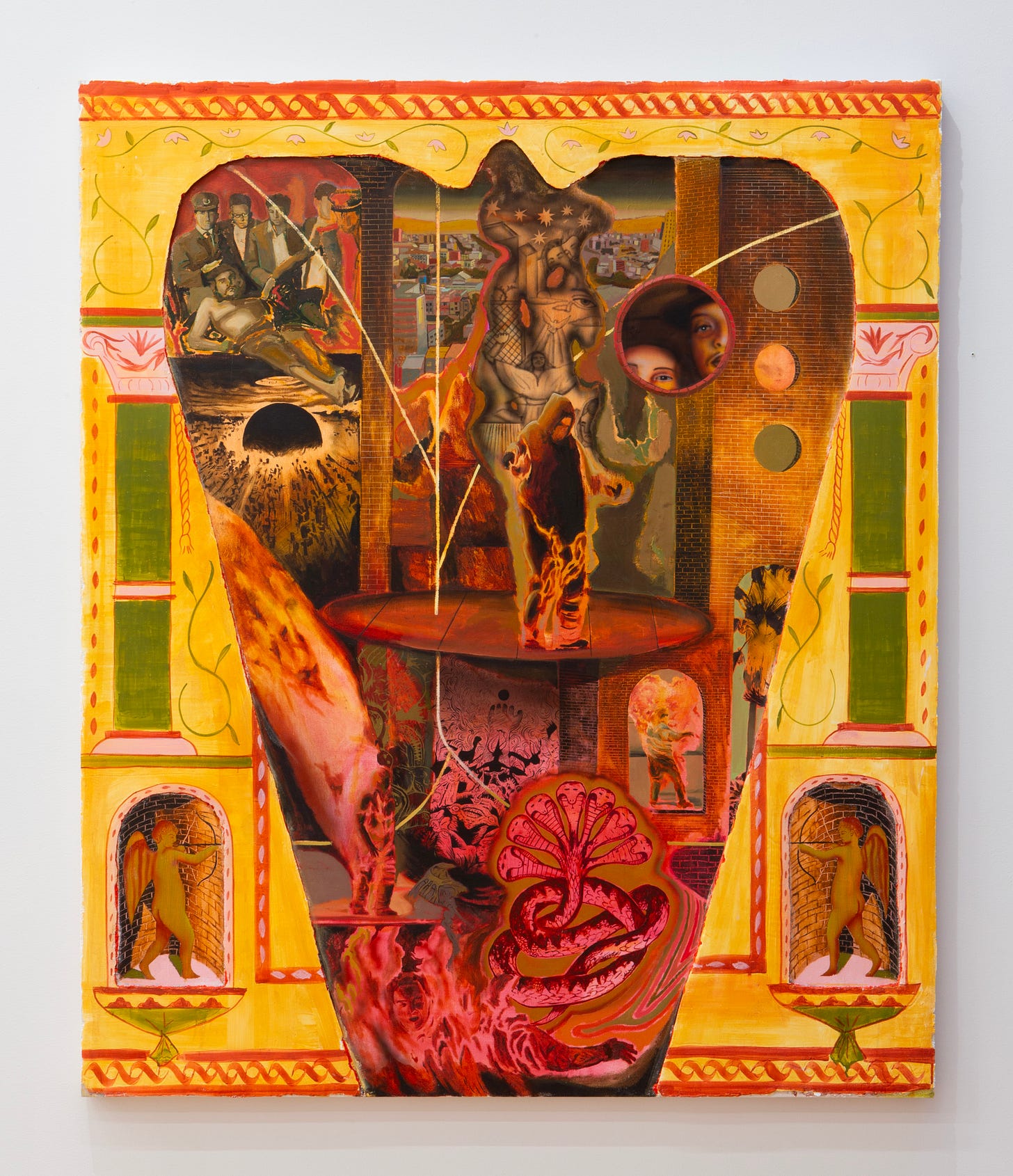

Jose de Jesus Rodriguez’s paintings require you to linger. His proclivity for maximalism is attention-grabbing. You find your eyes scanning for the meticulously placed symbols scattered across his canvases. The sepia tones in his art invoke a disarming sense of nostalgia and levity, yet the underlying themes are urgent.

“I always felt like I had to make work that justified me wanting to paint,” the artist explains. Jose grew up in Salinas, California, home to John Steinbeck, and known for its moniker as the “Salad Bowl of the World.” His parents are Mexican immigrants who worked on some of the industrial farms that saturate the valley. Their transition to the US was aided by continuity of work - they worked as farmers in Mexico, and they worked as farmers in the US.

However, this continuity meant that Jose’s desire to be an artist would take him down a path that was difficult to conceptualize in his youth. "Some of the very earliest tensions I felt as someone that wanted to be an artist was the labor itself, my ability to imagine the concept of work was rooted in seeing work where the body is very present,” he elaborates. By 22, Jose had committed to entering the art world as a professional.

This decision ushered in an intense introspection into his relationship with creative labor. Most artists aren’t blatantly exploitative in their praxis like colonial artist Agostino Brunias, or more tepid modern-day variants like Jill Greenburg. All the same, every artist pulls from their environment and the people around them, which (in varying degrees) is an extractive process. Further exploration into the dynamics of creative labor made it clear to Jose that, in many ways from production to selling, “art can easily become an exploitative or indulgent endeavor.”

Perhaps it’s his Catholic guilt, but it’s clear he feels a sense of responsibility to nullify the effect of this extraction by making it less self-serving. As an art student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP) emerged as a foundational inspiration for Jose in his quest to make a communal function of his art. The TGP, a Mexican avant-gardist printmaker collective, was founded in 1937 by Leopoldo Méndez, Luis Arenal, and Pablo O’Higgins. During the 1900s in Mexico, printmaking became a tool for political commentary on local socio-political struggles and international politics. The TGP’s 1947 print collection, Estampas de la revolución Mexicana, included a “Declaration of Principles”, highlighting the group’s dedication to art as a form of public service.

Making art as a public service forced an expansion of Jose’s artistic curiosity. “I had been working with safe references, from a safe position, making art about things that I can talk about with confidence,” Jose says. Now, he’s commenting more on socio-political touchpoints in popular culture - particularly about how public perception can be shaped, manipulated, and captured for profit.

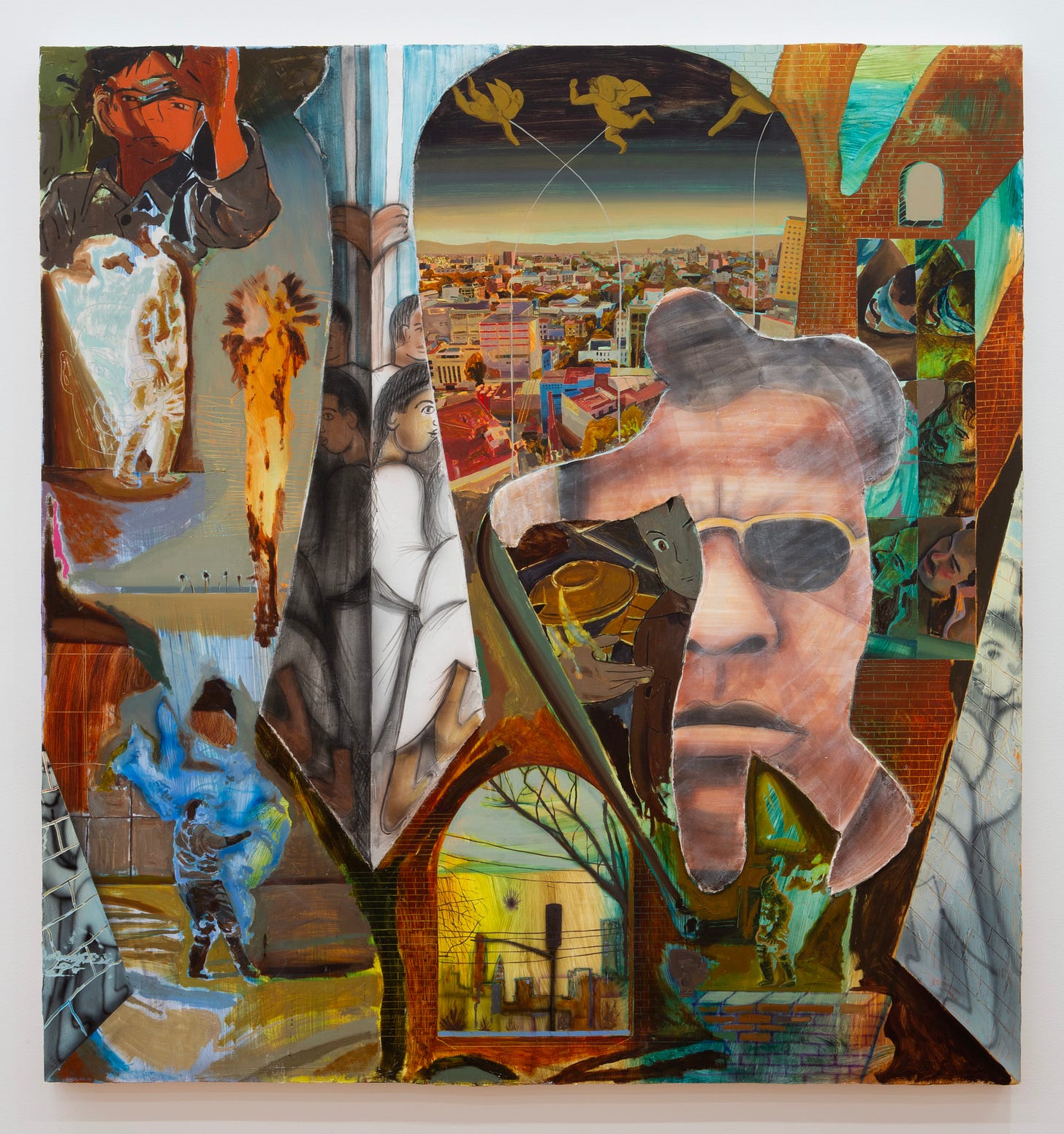

One of his newest pieces, Death to the Fascist Insect, is filled with apocalyptic motifs, images of people on fire or experiencing pain, but most poignantly, onlookers. The title of the painting itself is a reference to the manifesto of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA). The SLA was a leftist militant group active during the 1970s, catapulted into public consciousness after the kidnapping of Patty Hearst, the daughter of media magnate William Hearst. After her 1975 arrest for her involvement in SLA’s robberies, Patty was sentenced to seven years in prison, of which she served 22 months before her sentence was commuted in 1979 by President Jimmy Carter.

“There's a question of how we arrive at meaning, especially because at times we can’t look beyond what we want to see,” Jose explains. In the case of the SLA and Patty Hearst’s trials, how American society ascribed grace, justice, and punishment reflected the socioeconomic and political realities of the late 60s and early 70s. The SLA was destined to be buried under mainstream anticommunist sentiments even before their more violent tactics put them in the spotlight. Some of the most prolific left-wing groups of this era had internal issues with misogyny and sexually dubious behavior. Patty was a white, rich, young, heiress. All these factors impacted the narrative, and the subsequent fates of every member of the SLA, including Patty.

Ironically, the incessant sensationalism William Hearst ushered into the American mediascape was omnipresent in his daughter’s trial in the court of public opinion. Patty and the SLA whipped the media into a frenzy. They even televised the gun battle between the LAPD and the SLA - it was a ratings gold mine.

And that’s Jose’s point.

“It’s deeply insidious that even things like this can be part of the capitalist machine,” he points out. Every story has a dollar value. Every ideology can be recuperated, normalized, and institutionalized. The ideologies that the SLA espoused in their manifesto are now more commonplace fodder in online social spaces. Some members of these once-fringe leftist groups are now lauded academics, activists, and public figures. The machine absorbs and keeps going.

Reconciling with this notion of capitalist capture has transcended his art and spurred into a current internal crisis for Jose. Today, making art as a public service is not the same as during the TGP era, neither in the US nor Mexico. From his observations, bold political statements, even when they are rooted in solemn truths, are somehow still commodifiable. Inevitably, they are reduced and stripped of their significance, nimbleness, and rigor. They are no longer avant-garde.

The capture of the avant-garde doesn't necessarily translate to progress. Yet, it poses a problem of intention and necessitates a level of self-awareness difficult to cultivate in a society where your survival is intimately tied to your ability to make money. Imagine making art, hoping to inspire conversations about pressing issues or demonstrate a point about sociopolitical phenomena, while recognizing that whatever person or entity can afford the art is closer to robber barons than the average Joe. It can be quite an uncomfortable load to carry.

So, where do you put it all down? For now, it's still on the canvas. “I try to paint my little tiles, and drink a coffee,” he says. Jose is exhibiting more now. More people are seeing the art he creates about notions of community, his musings on identity, public perception, religion, etc. He’s been grappling with his meaning-making - how he curates and distributes his public image. “I’m getting away from language about my identity that previously rooted me, it’s not the most sustainable anymore, but how do you make sense of yourself when you’re around strangers?” he inquires.

While Jose is figuring it out, his profile is being established. Soon he’ll be receiving more requests for press releases and articles about his work like this one, asking him to describe his artistic philosophy. The therapeutic function of making art will suffice while the philosophical one is in transit. That’s all an artist can do, put paint to canvas, until it all makes sense.